The following is a loose transcript of a presentation I gave on Meek’s Cutoff, a film that was part of the Pickford Film Center’s repertory series, West of What?!, that ran from June 2017-May 2018. The presentation included a slideshow; the images below correspond to the slideshow images.

Good afternoon and welcome to the screening of the Kelly Reichardt’s 2010 film, Meek’s Cutoff.

Today’s film is a part of the Pickford’s West of What?! Westerns series, and, so before we begin the film, I’m going to talk for a little while about the film and its place in this series.

The Westerns genre is, of course, a significant part of the American cinematic landscape, and it was, for a certain period, enormously popular.

Between 1930-1954, approximately 2,700 Westerns were released. (Source: http://www.b-westerns.com/graphs.htm )

The Westerns genre, though, contained some troubling ideas or myths that are important to recognize.

For example,

For example,

- The genre often promoted myths of westward expansion – the idea of Manifest Destiny – this sort of God-given right (to white people) for westward expansion into the indigenous peoples’ land.

- It often defined a very narrow, traditional view of masculinity

- It presented often absurd, gender stereotypes for women. Women were often depicted as purely domestic beings, side characters mostly useful as a civilizing force over men

- It often normalized genocide, specifically of Native Americans

One of the most interesting things about Westerns is that the popularity of the genre might have a lot more to do with how many Americans tend to see and explain themselves (Looking at Movies, Barsam and Monahan), rather than with a connection to historical accuracy or to the true, often troubling, complexity of our country’s checkered history.

So one of the goals of the West of What?! series – given these things – has been to consider the problematic ideas or ideologies in the Western genre both by looking at Westerns that contain them and by looking at Westerns that subvert them in some way.

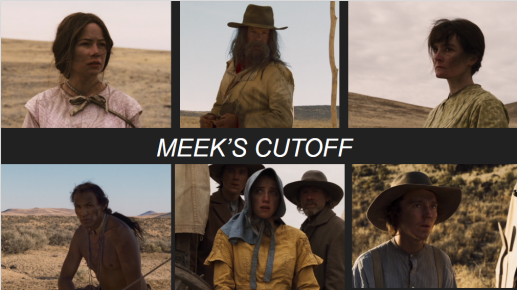

Today’s film, Meek’s Cutoff — starring Michelle Williams, Paul Dano, Bruce Greenwood, Zoe Kazan, Shirley Henderson, Rod Rondeaux — offers a particularly interesting entry into the Westerns genre in the ways that it meets the genre conventions but also completely overturns them.

Reichardt’s film might even be conceived as a sort of answer to some of the most troubling myths of the Westerns genre, but it is also, itself, unmistakably, a Western. . . .

(Continue reading at Seattle Screen Scene: Link )